In 2021, the National Council of Science and Technology (CONACYT for its initials in Spanish) opened a call for the project Basic and/or Frontier Science: Paradigms and Controversies. It supports researchers’ evaluations of paradigms, hypotheses, and theories that advance understanding of phenomena in various areas of knowledge, and financially supports projects that aim to analyze open access data (online) to provide a novel scientific perspective.

Rodrigo Sosa Sánchez, PhD in Behavioral Science from the School of Pedagogy and Psychology at the Universidad Panamericana, Guadalajara campus, with the support of Dr. Emmanuel Alcalá from the Western Institute of Technology and Higher Education (Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente, ITESO) and Jonathan J. Buriticá, Associate Professor at the Center for Behavioral Studies and Research (Centro de Estudios e Investigaciones en Comportamiento, CEIC) set out to participate in this call with a project on time estimation.

Time estimation

Time estimation (or interval estimation) is a psychological phenomenon that refers to the ability to structure our behavior according to the temporal regularities of our environment.

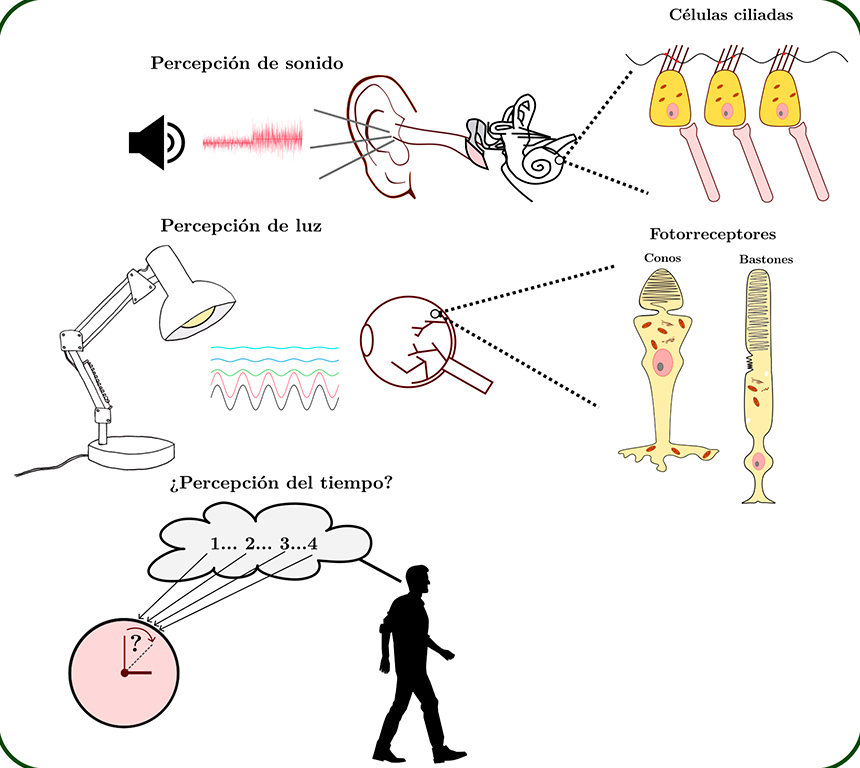

For many authors, this is an intriguing phenomenon since, biologically, we have receptors to detect light, sound, textures, and even chemicals that allow us to adapt to our environment, but we lack special receptors to detect the passage of time.

How do we estimate the duration of intervals? The short answer is that we have certain “pacemakers” in our nervous system that allow us to estimate (with a certain degree of error) the “when” of events occurring around us.

Our own behaviors sometimes also serve as pacemakers to tell us the right time to act; this is because we also have receptors to detect the immediate consequences of our actions.

How do we estimate time?

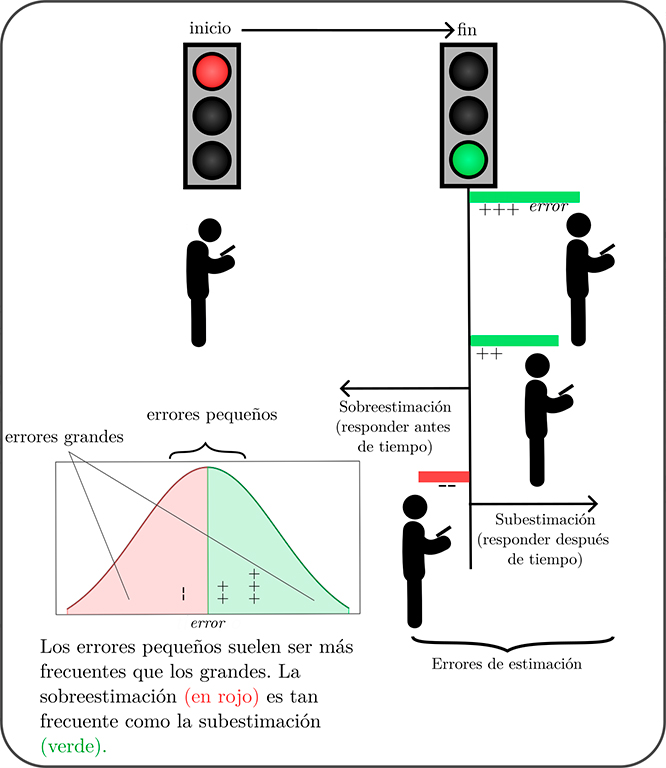

Dr. Sosa Sánchez explains that our ability to estimate time is involved in practically every sphere of our lives. For example, while driving home, we regularly stop at a crossroads when the traffic light is red. If we assume that the duration of the red light is constant, then this is a learning opportunity (we learn from the regularities of our environment).

In such a situation, to act effectively, we require a chain of two behaviors: (1) Looking to see if the light has changed to green, and then (2) stepping on the accelerator to continue on our way home. What do we do while waiting for the light to change from red to green? People do a variety of things, but the point is that, almost without exception, we will eventually turn to the traffic light to see if it is time to step on the gas or if we should wait a little longer.

“The interesting thing is that, while we learn, our errors are probably distributed like a Gaussian bell,” explains Dr. Sosa. That is, sometimes when we look at the traffic light, it may have already changed to green (we underestimate the passage of time) or it may be a fraction of a second away from changing (we overestimate the passage of time).

The purpose of the project

The spirit of this project, in Dr. Sosa’s words, is to describe the error correction mechanisms involved in order to gain a more accurate estimation of the intervals we regularly encounter. For example, if we take longer to turn to look at the traffic light, we may be honked at by the driver behind us and startled by the sudden noise. Or, again, if we look too soon, we interrupt our leisure activity or digression that was occupying us during the red light.

According to Dr. Sosa, the specific objective is to study beyond the organization of behavior when learning has already culminated, which is what has been studied in greater depth.

Namely, the researchers are interested in discovering the microstructure of learning by error correction and the individual differences in the disposition to learn from these temporal regularities. That is, the adjustments that individuals make moment to moment to adapt to the temporal attributes of their environment, as well as the persistent individual traits that distinguish particular individuals.

Support received

Dr. Sosa details that his CONACYT project involves accomplishing a series of outcomes, including publishing a scientific article with data analysis, participating in conferences and workshops, and confirming a repository with digital tools for the analysis of behavioral data (see https://github.com/jealcalat/YEAB).

At the same time, the Universidad Panamericana is supporting this project by facilitating space for Dr. Emmanuel Alcalá, Associate Researcher, who is now the head of the project, as well as organizing one of the conferences included in the scientific dissemination plan.

Contributing to how we understand behavior

Similarly, Dr. Sosa states that “the conviction to contribute to the understanding of behavior is what led us to carry out this research, since, on many occasions, one must step back and take the time to think about things differently, usually in an abstract and formalized manner.”

“This is a research project in basic science, i.e., science that lays the foundations for any field of knowledge, thanks to which we have the principles upon which to build a body of coherent knowledge, reducing our uncertainty about the universe around us,” he says.

He also points out that, in contrast, “frontier science or applied science proposes strategies to intervene in the phenomenon under study regarding some problem in today’s world. Although the latter attracts a lot of attention, it is important to emphasize that applied science cannot exist without robust basic science.”

“For the time being, we cannot get ahead of ourselves regarding the results, since project implementation will consist of decomposing the variance of time series estimation data from several individuals using hierarchies in terms of the units of analysis, moment-to-moment observations within a day or between days,” he states.

He also concludes that, “Roughly speaking, one expects to find certain regularities in how behavior is structured given temporal constraints. It will be interesting to find out which of the above factors accounts for a greater proportion of variance. In addition, we will identify what proportion of the variance is outside the scope of the factors being proposed, i.e., how much noise there is in the data.”

Research team

Dr. Rodrigo Sosa Sánchez, Head Researcher

Doctor in Behavioral Science, Level B Research Professor in the School of Pedagogy and Psychology, SNI Level I

UP Guadalajara Campus

Dr. Emmanuel Alcalá, Associate Researcher

Doctor in Behavioral Science, Professor in the Department of Mathematics and Physics, SNI Candidate

Instituto Tecnológico y de Estudios Superiores de Occidente (ITESO)

Dr. Jonathan J. Buriticá Buriticá, External Collaborator

Doctor in Behavioral Science, Associate Professor at the Center for Behavioral Studies and Research (CEIC), SNI Level I

Universidad de Guadalajara